In the 1960s, the Catholic Church fell afoul of the thirst for personal liberation. The reforming Catholic council of Vatican II shattered the Church’s confidence in its mission, while secularization – spurred on by liberalism triumphant – swept Europe. These changes were only felt at a popular level in the 1970s, when sexual freedom and a declining respect for authority finally trickled down to the masses. For millions of souls it was a heady age full of lingering regrets, like experimenting with LSD or voting for Jimmy Carter.

It was inevitable that the anti-clericalism of the decade would appear on film. Seventies horror cinema – best viewed with a keg of beer and lots of Monster Munch – is full of scathing critiques of the Catholic Church. Some of them are rather good. A typical example is Lucio Fulci’s Italian production Don’t Torture a Duckling (1972), in which a Catholic priest murders little boys before they can “come of age”. The priest is motivated by an obvious sexual lust for his charges, as expressed in a speech he gives while falling off a cliff: “They grow up. They feel the stirrings of the flesh. They fall into the arms of sin, sin that God easily forgives yes: but what of tomorrow? What sordid act will they commit? What sins will they enact when they no longer come to confession? Then they will really be dead, dead forever, dead for all eternity. They are my brothers … and I love them.” The priest’s killing spree is Lucio’s personal metaphor for a Church that won’t accept the social changes of the 1960s and let its congregation grow up into mature, self-governing adults. The message implied by having Barbara Bouquet appear naked throughout the entire movie is less clear.

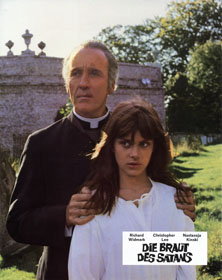

But closer study of the horror genre shows surprising nuance in the handling of priests. Two movies that deal thoughtfully with priesthood in an age of flairs are What Have You Done to Solange? (1972) and House of Mortal Sin (1976). The latter was directed by the brilliant Pete Walker, who had previously made some surprisingly conservative horror movies satirizing social reform (in one of them a cannibal is given an early release from prison for good behavior and, predictably, becomes a recidivist). House of Mortal Sin stars the wonderful Anthony Sharp as Fr Meldrum, the ultimate Seventies symbol of Church hypocrisy. Meldrum’s a traditionalist priest who refuses to say the reformed Vatican II Mass. He tapes confessions and uses them to blackmail parishioners into attending rough therapy sessions at his house where he shouts at them for enjoying sex too much. We learn that his mother forced him into the priesthood and refused to let him marry his childhood sweetheart. Sexual repression twisted into religious mania and it’s not long before Fr Meldrum’s off killing buxom young wenches in a variety of symbolic ways (strangled with a rosary, poisoned with a wafer etc).

So far, so liberal a critique. But at the emotional heart of the movie is a younger priest called Fr Bernard who has shacked up with Stephanie Beacham (well done, sir!). He’s toying with leaving the Church and parades all sorts of hip opinions about sex and drugs. Drippy Bernard is established by Walker as the hero, the man always on the brink of doing the right thing. But at the end of the movie, Fr Meldrum convinces Bernard to help him cover up the murders. He reasons that if the public knew what was going on, faith in the Church would collapse and all its good works would be diminished. Walker’s movie may be scathing of moral traditionalism, but he is equally condemnatory of Bernard’s cowardice and cronyism. The message: the sins of the past are excused rather than corrected by the timid liberalism of the present. Given the willful blindness that many “progressive” bishops demonstrated towards sexual abuse in the decades to come, it’s a remarkably prophetic vision.

The more nuanced What Have You Done to Solange? argues that the problem with the Church isn’t hypocrisy: its moral emasculation in an age of excess. The eponymous Solange is the daughter of the headmaster of a Catholic boarding school. At the start of the movie she’s a gibbering, idiotic wreck and no one seems to know why – or care. The school’s gym teacher, Enrico, is having an illicit fling with an underage student (but it’s okay, because both of them are hot). The two are cavorting in a rowing boat when they witness the brutal murder of one of the schoolgirls. Later, Enrico’s sexpot girlfriend is drowned in the bath for what she saw, forcing him to go on the hunt for the killer.

Director Massimo Dallamano encourages us to think that it’s one of the priests at the school behind the kinky massacre. A rosary is glimpsed and it is implied that the killer picks his victims whilst hearing their confessions. But Dallamano has a surprise for us. Enrico realizes that the villain isn’t picking on random girls but rather on former friends of Solange. At the film’s climax, he discovers that all the victims were involved (very willingly) in a sexy sex ring. Solange got pregnant and the schoolgirls forced her to have an abortion, performed with rusty implements on a kitchen table. Solange was driven mad by guilt. Her father, the headmaster, took it upon himself to avenge her by slaughtering everyone involved.

Dallamano implies that the Church is partly at fault for not having chastised the schoolgirls and enforced moral order. The priests on screen are nice enough fellows, but presented as tired and confused; the schoolgirls regularly skip Mass and no one notices. The headmaster represents an outraged laity that must take order into their own hands. Given the awfulness of the abortion scene, the audience is prompted to sympathize. What Have You Done With Solange can be read as a sort of prolife response to It’s Alive!, a traumatic movie about a baby born with a taste for human flesh.

Solange and Ducking really belong to the early 1970s, when Freud’s influence was still felt in Europe's studios. But something changed in the horror genre mid-decade. Take the movies of Dario Argento, the master of Italian schlock. His early efforts (Bird with the Crystal Plumage, Deep Red) feature human villains motivated by sexual angst. By the end of the 1970s, he was making movies like Suspiria and Inferno, in which the culprits are witches. The popularity of the theme peaked in the mid-1980s with two movies he co-produced called Demons and The Church. Both feature literal demonic infestation, usually beaten back by cool black dudes on motorbikes. In the course of a decade, audience tastes had gravitated from Hitchcock to Edgar Allen Poe.

That slow change was reflected in the wider depiction of priests on film. In 1973, Warner Bros released The Exorcist. The movie depicted two priests; one modern and skeptical, the other a traditionalist mystic. It is the mystic, with his peculiar Latin rites, who is revealed to be correct about the demon possessing foulmouthed child actress Linda Blair. The hysteria surrounding the movie helped revive the Church’s reputation as a force for good. Its medieval understanding of pure evil, which seemed so anachronistic in the 1960s, was now terrifyingly hip. The release of The Omen in 1976, in which Satan is incarnated as a child, further underscored the triumph of Catholic mysticism. The movie features a batch of apostate priests, but there’s no doubt that it is Catholic dogma that holds the key to repelling the Antichrist. Both movies coincided with the American Fourth Great Awakening and a worldwide revival of religious evangelicalism that offered an escape from the economic miseries of the late 1970s. Alas, the Moral Majority typically campaigned against horror movies on the grounds of violence or explicit sexuality. They missed a trick. Many of the video nasties they opposed were infused with the religious sensibilities of the era. If only they had forced themselves to watch them, they would have realized that most were recruiting films for the Catholic Church.

Of course, individual movies and their directors don’t speak for the entirety of mass culture. But the improving screen image of priests does hold out hope for our current generation of clerics. History and culture don’t always progress forward; shocks to the system can spark social revolution, but they can also help resurrect orthodoxy. In the sexy, violent world of 1970s horror, everything old was new again.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed